Aux armes · a glossary of heraldic terms

‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.’

‘The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’

‘The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be Master — that's all.’Lewis Carroll (1871). Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There.

The following aims to explain the recondite terms used on this website. Although its scope extends to other closely related terms, it is not to be taken as a comprehensive glossary of English heraldry. Likewise, this should not be cited as authoritative, since its author is neither an historian nor an expert in heraldry and has merely cobbled this together from several sources. See: bibliography.

Achievement of Arms: a composition of a person's armorial bearings and all its adjuncts: the shield with its charges, crest, helm, mantling, mottos and, if present, supporters, insignia of rank or honour and the standard. As a form of disposition its origins are in the decoration of personal seals in the late-fourteenth century (Figs. 1 & 2).

Affronty (from Old French affronter, to the face, from Latin ad frontem, to the face): an heraldic attitude (q.v.) of beasts and birds as charges, crests or supporters, facing towards the observer.

Argent: silver, by convention shown as white — an heraldic tincture.

Arms: exclusively the field and its charges as borne on the shield of arms, banner and caparison (q.v.). Each arms must be distinctly unique. They are distinguished from earlier forms of military paraphernalia in being subject to systematic rules governing their design and in their restricted heritable use as personal emblems.

Azure: blue — an heraldic tincture. The particular qualities of the colour, such as lightness, saturation and precise hue, are not prescribed and in practice these were of great variety, but it has long been shown in British arms as a shade of rich dark blue. Some early French blazons admit differentiations for ‘azur bis’ and later ‘azur foncé’ as dark shades of the colour, while ‘azur celeste’ (sky blue) was introduced for lighter shades in post-medieval arms.

Attitude: the position, pose or configuration in which an heraldic creature is shown. Before the early-fourteenth century attitudes were not blazoned in English arms, but the later proliferation of arms necessitated an increase in the pool of distinct images: the discrete variations offered by attitudes was the ingenious solution.

Badge: a freely adopted personal emblem or device. The use of badges was widespread and vastly predates heraldry.1 Despite this, they were not found in the panoply of medieval arms until the innovation of livery badges and standards (infra) during the reign of Edward III (1327–77). Thereafter their use was common in England throughout the late Middle Ages, even though at various times their display was suppressed or restricted when some of their bearers threatened Royal authority. Although badges sometimes incorporated a figure or device from the crest — but never with the wreath or crest-coronet — they were predominantly wholly distinct from the arms or crest. The simultaneous or sequential use of several badges by individuals was common throughout the Middle Ages.

Only since the early twentieth century have badges been incorporated with English arms or granted as a later augmentation. Before then the practice was unknown, except for a single instance from the early-sixteenth century. Even so, the College of Arms did not arrogate to itself exclusive privileges over heraldic badges and such incorporations remain entirely optional.

Banner: a personal flag, usually square or nearly so, always with the arms alone displayed over its entire surface (Fig. 3) — the display of the crest, shield of arms, motto, et al on a banner is an occasional recent solecism, inevitably with visually incoherent results.

They were perhaps the precursor of all heraldic devices: the earliest arms (from the mid-twelfth century) were on banners rather than shields or coats of arms.

IIlustrations from the High Middle Ages show them with diverse proportions, usually between 3:2 (vertical:horizontal) and square. From the Tudor period onward the free edges of banners were frequently embellished with fringes of gold or alternating sections of the principal colour and metal of the arms — although now prevalent, this practice was always merely decorative and never canonical.

Bearer: the personal holder and possessor of the arms.

Blazon: a definitive description of a composition of arms, crests and other heraldic emblems. The terms are set out in a rigidly prescribed order, without any punctuation. Any depiction of arms is subordinate to its blazon. This paradoxical dominance of the written form over the pictoral allowed the space and freedom for heraldic art to flourish and develop into one of the minor glories of the Middle Ages.

The blazons of English heraldry derive from a macaronic amalgam of Middle English and Norman French, with the grammatical structure of French being dominant — for instance, most adjectives are placed after the noun. However arcane and inscrutable it may seem, this is a concise and precise language of occasionally ingenious subtlety and adaptability, and one with perhaps an undeserved fustian reputation. Despite the borrowed vocabulary and common grammar, in French heraldry the arms would be blazoned otherwise: D'azur semé d'étoiles à six rais aboutées et accolées d'argent.

Early blazons were confined to the arms as displayed on the shield and are often characteristically concise: d'azur poudre a molets d'argent is anachronistically in this manner (Fig. 4). The preponderance of Old French is striking in them, as is the irregularity of spelling, which is sometimes inconsistent even within the same document. The general paucity of Arms, meant that terms for precise configurations and details were uncalled for, hence such niceties are absent from early blazons.

Cadency marks: a system of small charges applied to ‘difference’ (that is, to differentiate) the arms of members of the same family. They were an innovation of the College of Arms in c. 1500: but, except for the label (q.v.), which predates this innovation, they were widely disregarded until the mid-nineteenth century and the advent of fervid medievalizing. Their tinctures are unregulated, but always contrast with those of the arms.

Canting Arms (from Norman French canter, from Latin canere, to sing): arms containing an allusive visual pun or rebus on the name of the bearer.

Canton: the first quarter of the field of a shield, that is, in the dexter (q.v) chief (q.v). Conventionally shown as about three-fourths of that quarter, it almost always bears a charge or charges.

Caparison (also horse-trapper): the cloth coverings of a war-horse, usually charged with the arms of its rider. (Fig. 5)

Chapeau (also cap of maintenance): A cap with a turned-up brim surmounting the helm and supporting the crest, common in early arms. When a cap of maintenance it is in crimson lined with ermine, its use is restricted to royalty and members of the peerage. In the arms of commoners they fulfil the role of the wreath (q.v.), with the colours following rule for the latter, i.e. with the outer surface being of the principal tincture and the lining the metal. In later versions it is often shown with a split, swallow-tailed, rear portion, in a departure from the original form, which is always undivided.

Charge: an emblem or device set on the field of a shield, banner, crest or supporter.

Chief: the uppermost third of the field of a shield.

Coat of Arms: originally simply the Arms (as on the shield and banner) when set on a knight's surcoat or jupon (a short sleeveless coat, Fig. 5) worn over armour, but now synonymous with the Achievement of Arms — however, the entire Achievement of Arms was never applied on coats.

Conjoined: of charges, abutted.

Couché / couched (from Old French couchier, to lie down (lit. to go to bed), from Latin collocare, to place, assemble): of a shield, tilted at an inclined angle: a common early practice reflecting the alignment of the shield when carried in combat (Figs. 1 & 2).

Crest: an emblematic figure fixed to the top of the helm, usually mounted on a wreath or crest coronet — unlike a coronet set above the shield, the latter does not signify rank. As with Arms, their design is required to be unique. The earliest recorded crests are from the late twelfth century, but their ubiquitous use, complete with helm (q.v.) and mantling (q.v.), followed the adoption of a crest by Edward III in the early fourteenth century.

Displayed (from Old French despleier, to unfold, from Latin deplicare, to unfold): the attitude of an eagle or other bird of prey, with wings and legs spread wide. Blazons from the reign of Edward III (1327–77) have the Old French espanie, which was used for arms showing eagles with expanded wings either elavated or inverted. The term wings expanded was more often used where the wings alone were shown spread, with the legs in a natural disposition.

Doubled: used of mantling, lined with.

Enumerated charges: where multiple (but not semé) charges are shown these are enumerated from the top downwards. Thus the stars in the flag of General George Washington as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War of 1775–1783 would be blazoned … three two three two three ….

Entoured (from Old French entourer, to surround): surrounded by, encircled by. Environed (from Old French environner) is synonymous.

Estoile (from Old French étoile, a star): a charge, in English heraldry, a star with wavy rays (or sometimes alternating with straight) rather than straight points as in the Mullet. If not with six points the number is specified in the blazon. In Scottish, French and German arms heraldic Stars have straight points and are identical with Mullets, usually of six-points.

Expanded (from Latin expandere, to spread out): the attitude of an eagle or other bird of prey, with wings spread wide, but, in distinction to displayed (supra), with the legs in a natural disposition. In post-medieval blazons ‘wings displayed’ is frequently used to the same effect, although this was absent from earlier blazons.

Field: the surface of a shield or banner. Its colour is the first item described in a blazon, followed by the charges on it and then their colours.

Fracted (from Latin fractus, past participle of frangere, to break): of ordinary (q.v.) charges, having a part displaced, as if broken: of other charges, broken.

Helm: a helmet, an heraldic accessory set above the shield of arms and bearing the crest. The type displayed varies with the rank of the bearer: only the closed or tilting (tournament) helm in steel is used in rankless commoners' arms and although later these are often depicted with embellishments, this ornament is of no significance. Such distinctions “befittinge degree” were introduced in the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603), before then a plain tilting helm in profile or affronty (q.v.); was universal (Figs. 1 & 2).

Label (from Old French lambel, a strip of cloth): a cadency mark: a narrow transverse band with points (pendant vertical tabs) placed in chief (that is, in the uppermost third) of arms. The appropriate label is also normally applied to the neck (when shown as a collar it is blazoned as gorged with a Label …) or chest of any beast or bird in the crest (Fig. 6) or supporters.

First used in the mid-twelfth century, it is an early cadency mark and remains the only one widely applied in English arms. Five points was usual in early labels, although their number was then arbitrary. Later three points are presumed, otherwise the number is specified in the blazon. Henceforth, with three points it differenced the arms of an eldest son from those of his father (Fig. 7); on the death of the father the label was removed from the arms of his son. The eldest son of an eldest son — or the eldest son of an eldest daughter, if she had no living brother, that is, she was an heraldic heiress — had a label of five points set on the arms of his then living grandfather. Even so, labels with five points continued to be used in the arms of both younger sons and grandsons, with various small charges added to some or all of the points for further differentiation.

Mantling (lambrequin): drapery tied to the helm beneath the wreath, in commoners' arms this is usually of the principal colour in the arms lined with the principal metal. Except in some renderings of early arms, it is usually shown with stylized ‘ragged’ edges. Some have claimed this embellishment mimicked the torn edges suffered during combat, but scalloped hems were also fashionable on clothing of the period and thus it might have been that mantling merely followed that fashion. Tudor period mantlings became increasingly mannered and bizarre: thereafter they were composed for decorative effect, in contrast to formerly more naturalistic representations (Fig. 2).

Motto: an epigrammatic or allusive expression whose origin is the cris-de-guerre (battle-cries) of the fifteenth century. Although normally shown in the depictions of Grants of Arms, they are not blazoned in English heraldry. Their selection and display has at all times been subject to the absolute will of the bearer alone — likewise, any subsequent bearer may freely alter a motto. In English custom, the motto is not required to be unique nor does its prior use preclude reuse in other arms.

It is typically placed as if on a scroll below the arms, but if there is a second motto it is customarily set on a scroll above the crest — this latter form is also the practice for singular mottoes in Scottish arms, where mottoes are blazoned as an integral part of the arms and so remain exclusive to the bearer.

Mullet (from Old French molett, of obscure etymology2): a charge, a straight-sided star polygon. If not of five points the number is specified in the blazon. In early English arms the number was indeterminate and never blazoned; both five and six points being equally common and seemingly interchangeable, sometimes different renderings of the same arms used either. In distinction, the charge with six points is the predominant form in French and Germanic/Nordic heraldry. They may be entire or pierced/voided (that is, with a central hole, as if in a spur rowel), but if pierced they are blazoned as such (supra estoile) — in Scottish heraldry, un-pierced mullets are blazoned as ‘stars’.

With five points and un-pierced in English arms it is also a cadency mark for a third son, most commonly seen in nineteenth century arms.

The term mullety/mulletty is a neologism for a semy of mullets: evidently in the manner of the established practice of bezanté (semy of bezants), crusilly (semy of crosses), etc. Its historical basis is spurious and it is absent from authoritative blazons.

Or: gold — an heraldic tincture.

Ordinary: a simple geometrical charge, bounded by straight lines and running from side to side or top to bottom of the shield.

Orle (Old French orle, to hem, from Latin ora, margin, edge): a narrow border of a Shield, inset from the edges of the shield. In Orle: small charges arranged after the manner of an Orle, that is, as if set on an inset border. Eight such charges are assumed, otherwise the number is specified in the blazon. With an Orle of …: used for an ensemble of small charges surrounding another charge.

Poudré (also poudre) (Old French poudré, powdered with): identical with semé (q.v.), it was prevalent in early blazons.

Sans nombre (Old French sans nombre, numberless): identical with semé (q.v.), sometimes found in early blazons.

Proper: of charges and supporters, rendered in their natural forms and colours.

Scroll (also escroll): in a depiction of arms, a ribbon charged with the motto. Unless borne as a charge in the arms or on the crest, they are not blazoned in English arms, as otherwise, as with the motto, they have no heraldic significance.

Semé / semy (from Old French semée, sown): strewn with unnumbered identical small charges, uniformly distributed over the entire field or on another charge or supporter. Its alternative spellings — semé, the original French, and semy, an early anglicised form — were both common and often various recordings of the same arms used either.

As they are treated as variations of the field, fragments of semé charges should appear at the borders of the shield or banner. However, from the evidence of surviving rolls of arms, heraldic artists did not consistently abide by this rule and sometimes omitted the fragmentary charges altogether — although whether this followed from economy of execution, rather than accurate recordings of the arms themselves is uncertain.

Semé is a versatile designation and may be applied to crest elements, charges and supporters as well as the field.

Shield (from Anglo-Saxon, scyld/sceld, a shield): a freely-wielded armoured surface borne on the un-weaponed arm of a warrior as a primary means of defence. Its origins are remote in pre-history, as is the practice of marking them with distinctive patterns or emblems. The ephemeral personal devices sometimes seen on earlier Norman kite shields (Fig. 8) follow this tradition and are doubtless precursors of heraldry, although the earliest incontrovertible heraldic emblems on shields are from the mid-twelfth century. Likewise the distinctive shape of the heraldic shield (Fig. 9) is derived from those Norman exemplars, although later this formal clarity was obscured with a fashion for grotesquely elaborate shields during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Standard: a long tapered flag with the fly (free) edge rounded or swallow-tailed. Introduced in the middle of the fourteenth century, evidently for the specific purpose of displaying the badge and, later, the motto. In the Middle Ages, the field and alternating sections of edge fringes were of the livery colours, which were not then necessarily related to the tinctures of the arms. Early (English) examples had the arms of St. George (a red cross on a white field) next to the hoist (adjacent to the flagpole), but somewhat later the arms of the bearer were used and their crest was sometimes substituted for the badge, with the field displaying the tinctures of the arms.

Supporters: figures flanking the shield as if supporting it. Except as entirely decorative devices in seals of the late fourteenth century, they were rarely seen before the mid-fifteenth century. There they invariably flank or ‘support’ the Helmet, rather than the shield (Figs. 1 & 2) — indeed, on the contrary, they are usually shown supported by the shield set couché (q.v.). Their subjects are highly diverse, encompassing real or imaginary beasts, birds, fish or human figures. During the Elizabethan period the right to display supporters was curtailed and restricted by rank, henceforth they were no longer used in the arms of rankless commoners, except by prior ancestral right.

- Tinctures (see note 3: the rule of tincture): heraldic colours, metals or furs — the latter are represented in conventional and highly-stylized patterns. The colours and metals are:

- The metals:

- Argent: silver

- Or: gold.

- The colours:

- Azure: blue

- Gules: red

- Purpure: purple *

- Sable: black

- Vert: green.

* Purple is not represented in British arms until the modern period.

- The metals:

Wreath (torse): a spirally-wound ring of two rolls of cloth, usually shown as six alternate twists of the principal metal and colour in the arms, with the metal first on the dexter (right-hand to the shield bearer) side. It was fixed to the upper part of the helm, providing a means of attachment for the crest. It is seldom present in early crests, especially when the form of the crest could be readily merged into the mantling, as with the heads of birds and beasts cropped at the neck.

- Charles Boutell (1867, 1914). The Handbook to English Heraldry.

- Gerard J. Brault (1998). Early Blazon: Heraldic Terminology in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. Boydell Press.

- Arthur Charles Fox-Davies (1909). A Complete Guide to Heraldry.

- Anthony Richard Wagner (1956). Heralds and Heraldry in the Middle Ages. Oxford.

Figure 1: the seal of Edmund de Mortimer, 1400

Figure 2: the seal of Sir Richard de Beauchamp, c.1403

Figure 3: a banner

Banners comprise the Arms alone.

Figure 4: d'azur poudre a molets d'argent

Figure 5: a caparison and jupon in the seal of Sir Thomas de Beauchamp, 1344

Figure 6: a crest with a label

Figure 7: an early label: the arms of the Lord Edward (the future Edward I), as heir to Henry III of England

Coeval blazon:

goules trois lupards [leopards] d'or ovecque ung labell d'azur.

Later blazon:

Gules three Lions passant guardant in pale Or a Label Azure.

Note: the blazon does not describe the lions as “armed and langued Azure” (with blue claws, fangs and tongues), this was implicit: lions were presumed to be “armed and langued Gules” unless on a field gules (red), in which case, the former was implied. Nor does it set the number of points on the label, these were arbitrary during the period (1239–72) and various renderings of these arms display labels with three or five points.

Without the label, these were the Royal Arms of England from 1198 to 1340, whose first recorded use is in the second Great Seal of Richard I, Cœur de Lion.

Figure based and licensed on this source: Sodacan (2010). Royal Arms of England (1198–1340). Wikimedia Commons. CCL.

Figure 8: Norman ‘kite’ shields in the Bayeux Tapestry (c. 1077).

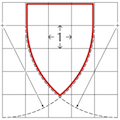

Figure 9: the setting-out of a characteristic late 13th century heraldic shield.

This setting-out is indicative rather than definitive, as there was no canonical method and the proportions of shields were throughout highly variable, even contemporaneously.

See: The Dering Roll (c. 1270–80).